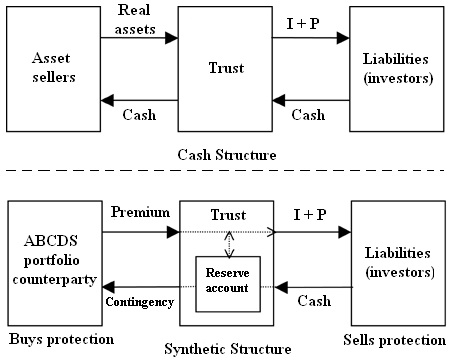

Synthetic structures can be built entirely out of CDSs rather than real assets. In a typical cash deal, the investors pay cash that is used to buy real assets in the collateral portfolio. The assets throw off interest and principal payments (I + P). These are paid through a waterfall to the investors. The issued bonds amortize at the natural rate of the collateral amortization.

This description is simplified in many areas. No prior funding of assets is assumed—it is as if all the assets were purchased at settlement. In reality, most assets are purchased beforehand, and this requires funding. There is some counterparty off to the left that funds the deal at some funding rate, and is paid off on settlement date by the investor’s cash. Also, on settlement, all assets are assumed to have been purchased—in reality, there may be a pre-funding period. There may also be a reinvestment period, which is assumed here to be absent. Finally, termination conditions are ignored. These same simplifications are assumed when considering the synthetic deal next.

In a typical (funded) synthetic deal, the investors pay cash to buy bonds. This cash is invested in relatively risk-free securities (reserve account) that pays a floating rate (London Interbank Offered Rate [LIBOR]). A portfolio of (AB) CDS is entered into. These swaps pay fixed premiums. Supposing the issued bonds are floaters, the premium (from swaps) plus LIBOR (from the reserve account) combine to form the interest payment to the bonds. Any excess interest goes into the reserve account. During amortization, cash from the reserve account is paid out as principal to the bonds. The amortization rate tracks the amortization rate of the (AB) CDS reference bonds. Should losses be taken in the reference bonds, the reserve account makes a contingency payment to the swap counterparty.

Finally, any cash remaining in the reserve upon termination is distributed to the residual. This type of synthetic structure is called a “funded” deal because bonds are issued for cash. The trust has been created to ensure that the assets in the reserve account are bankruptcy remote. It is possible to issue an unfunded tranche if the investor is so highly rated that it can be trusted to make contingency payments. Such a tranche is usually (but not always) the senior-most, called the “super senior,” that is, effectively rated even higher than AAA. The super senior is supported directly by entering into a CDS; that is, the investor pays no initial cash. What are the advantages of a synthetic structure? Primarily, it should allow optimal asset selection without having to bid on newly issued asset portfolios or bonds. Assets on the secondary market can be evaluated, compared, and selected prior to execution. A cash portfolio organically grown over time is perhaps less optimal. Also, synthetics enable cheaper funding.

CDSs can be cheaper than their corresponding cash assets. In addition, unfunded “super seniors” have lower spreads than funded seniors (hence are cheaper to the issuer). What is the main disadvantage? (AB) CDS counterparties to buy protection must be found, which may not be easy. A bespoke tranche (also called a single-tranche CDO or STCDO) is a synthetic structure consisting of a single tranche. It is simpler than a traditional synthetic structure (above), and can be optimized to an investor’s preferences. The investor can specify the collateral, the amount of credit enhancement, and the tranche width. If there is only one investor, then there can be no conflicts of interest with other investors, for example, the seller/ structurer who often retains the equity.

This can result in increased spread to the investor for equivalent risk. One investor also implies that the deal can be closed even faster than a traditional synthetic deal. Unlike a structure in which the seller has sold all tranches and hence holds no risk position, if the seller sells a bespoke to an investor, then the seller is short risk (i.e., it has bought protection). To hedge this, the seller may choose to sell protection in the right ratio (more about this in section 7). Either the entire index, a sector within the index, a subset of individual names in the index, or a combination of these can be sold as the hedge. A seller retaining the equity tranche of a cash structure has a similar hedging problem, as does any investor in any tranche.

Comments